Chris Cornell and Donna Summer died on the same date, five years apart.

Notes on impressive voices-as-instruments.

Donna Summer died five years ago yesterday.

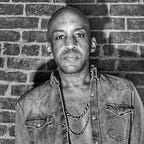

Before realizing that Temple of the Dog, Soundgarden, and Audioslave lead vocalist Chris Cornell passed away yesterday at the age of 52, Facebook told me that Donna Summer died five years ago on the same damned date. It was at this point that I knew that we needed to have a conversation about the importance of the voice in not just the articulation of lyrics, but moreover as an instrument that turns the spectacular into the transcendent.

Donna Summer was blessed with a finely trained three octave mezzo-soprano vocal range. Thus, there’s something very traditional about her voice-as-instrument that made it important in the very non-traditional world of disco. Summer came into the genre as a classically trained singer, and furthermore had starred in an off-Broadway run of the musical Hair prior to becoming a pop artist. Therefore, as compared to say, pornographic film star-tuned-vocalist Andrea True, or even throaty soul-funk growlers LaBelle (Nona Hendryx, Patti LaBelle and Sarah Dash), there was something to what Summer did vocally on tracks that really felt majestic in an almost regal sense.

Chris Cornell uniquely wavered between a not-so-classically trained tenor/baritone, having an almost range-free voice-as-instrument that differently from Summer, surprised and awed us all with its incredible flexibility. Thus, for grunge, this seemingly soulless thousand-yard stare into the cultural wastelands of Generation X, Cornell’s soulful wails were a standout. Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love’s, stardom was made via their anguished screams clashing with vitriolic guitars and drums. Comparatively, Cornell’s excellence was defined by the awkward, druggy stumble of a man’s heart — moreso than his head — trying to connect with his, or anyone’s body and mind.

Maybe it’s because we value the work of bands as hand-to-object instrumentalists so much, lauded the singer-songwriter as its own unique skill, plus maybe even not contemplated synesthesia and pop psychology as serious musical science that we lose a sense of the importance of the voice as an instrument. Guitars, drums, and other instruments have a plethora of tones that, when struck, create tones that spark dynamic emotional responses in people. There’s a sense that, even in adding electronic instruments to this mix, that you’re still working with yes, an ever growing, but also yes, a finite set of tonalities. It’s when you add the voice as instrument to that mix that things get intriguing.

Donna Summer and Chris Cornell stood out because their voices occupied spaces that all of the known available tones of all of the known available instruments could not reach.

When you listen to “Love To Love You Baby” and “I Feel Love,” it’s Summer’s voice being involved that’s the most important thing. Via her voice’s ability to discover a soprano register that both seems and feels higher than the well-established sonic register, she created what was in effect, the sense of a never-ending human sexual orgasm. There’s something as well in the color of her instrument, the “hue” of her voice that in not being bold or flat, but rather pastel in it’s “color,” allowed for the sacred and profane to combine in a manner similar, yet wholly different to say, Ray Charles’ Baptist sermon-esque rasp on his 1959 classic “What’d I Say.” In her voice-as-instrument elevating the art of making love into an angelic maneuvers in the dark as opposed to a hard, nasty, and oftentimes ribald act, she excelled.

“Hunger Strike.” “Black Hole Sun.” “Like A Stone.”

Imagine if somehow John Lennon and Al Green survived being strung out and started singing their hit songs. Imagine what well, because of the aforementioned circumstances, “Imagine” or say, Green’s take on Hank Williams’ “How Can You Mend A Broken Heart” were turned into dirges. That’s what made Chris Cornell’s instrument so mesmerizing. He was an artist-as-talent who combined Lennon’s ability to leave so much white space around his voice — as if he were delivering a song like the most epic civil rights speech — melded with Green’s desire to seduce every note he breathed and lustfully hold it until the last possible second. Note as well that the wear and tear of well, abuse, is present in that sound. Said abuse then colors every song, no matter the hues the tones recall, a fascinating, yet morose shade of gray.

Unlike Summer whose voice was blindingly brilliant when placed on, well, pretty much anything, Cornell’s voice was best in certain spaces. When blending its spellbinding level of existential angst and physical pain with grunge’s punk and metal-derived hard charging power rock chords and say, straight up and down bluesy drumming the likes of which were de rigueur in the days of say, Led Zeppelin, Cornell was a transcendent vocalist like none other.

I mean, there’s also when Cornell’s soulful clarion call would get quiet, like this cover of Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” or Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U.” When someone can speak words with tones that supersede being lyrics aimed at your ears, but rather emotive intonations to your heart, it’s incredible.

Donna Summer and Chris Cornell died on the same date, five years apart. The voice is an instrument, and when people die, their voices are instruments that are sadly silenced forever.